Synthetic Therapist Exoskeleton with LSTM

Featured Video

Objective

This project aims to improve post-stroke patient walking gait in rehabilitation using a lower-limb exoskeleton with implementation of a machine learning model trained on patient-therapist interactions. The ‘Synthetic Therapist’ would take the place of the human therapist in an exoskeleton rehabilitation system providing predictions from the model as inputs to the patient exoskeleton control loop.

Outcomes

System Architecture

The Synthetic Therapist successfully utilizes a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model trained using PyTorch to accurately predict therapist reactions to patient joint inputs.

Control loop for Synthetic Therapist rehabilitation system.

Closed-Loop Function

While active, the wearer of the exoskeleton (ExoMotus-X2, Fourier Intelligence) has their gait assisted and corrected based on outputs of the LSTM being fed into the patient exoskeleton control loop.

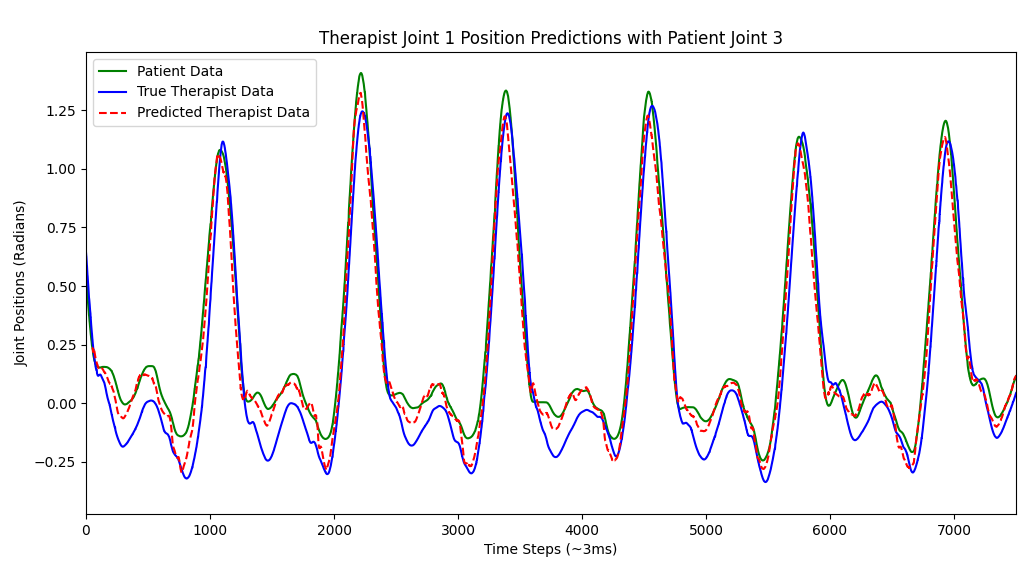

Example patient and therapist data with predictions overlayed.

The Synthetic Therapist runs on a ROS node within the workspace. The model receives input joint positions and velocities from the subject exoskeleton then publishes the output of the LSTM, predicted therapist joint positions and velocities, in real-time to maintain requirements of the human-exoskeleton interaction. An average inference time less than 3 ms allows for a smooth adjustment to the wearers gait.

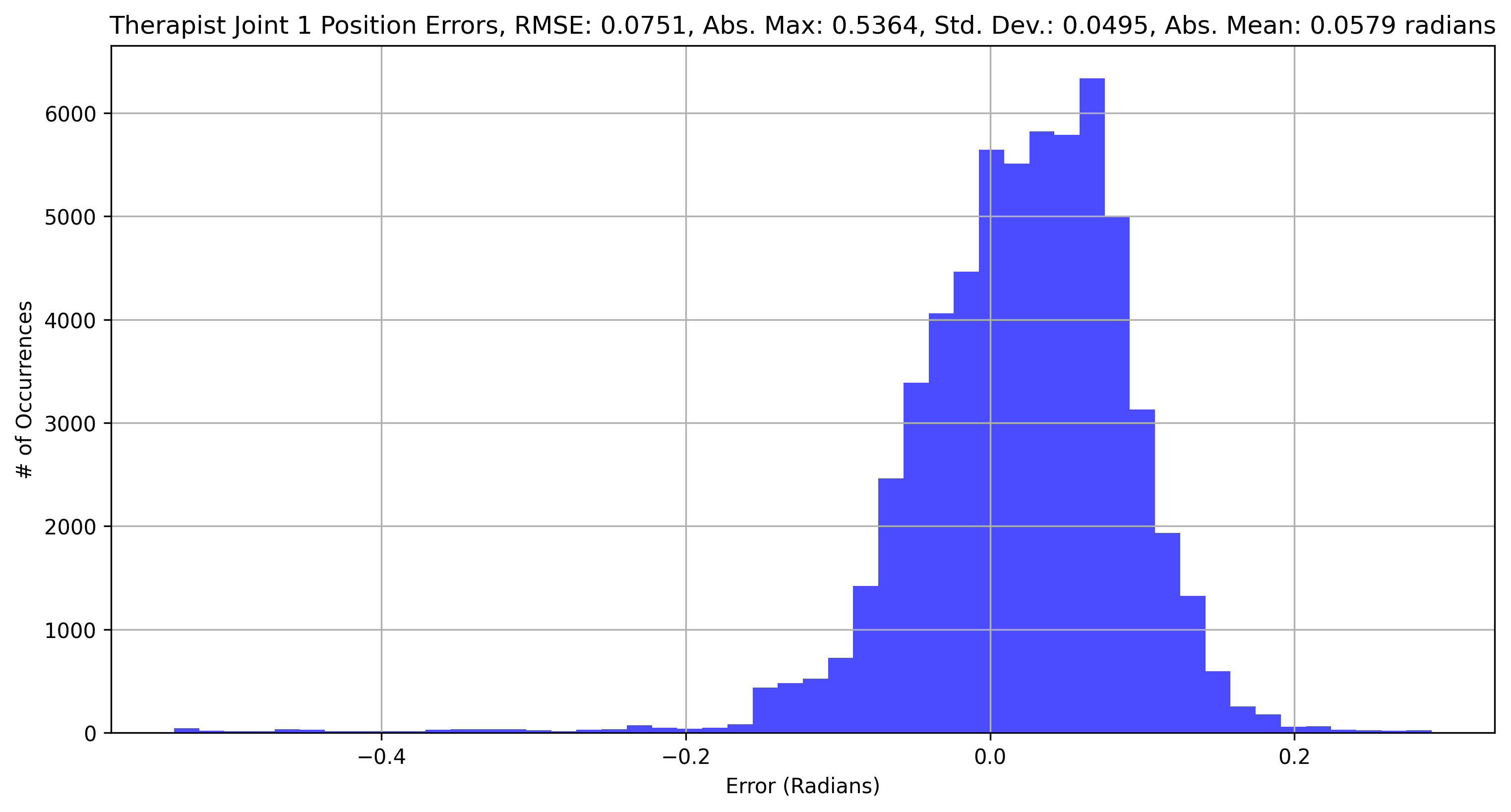

Prediction Accuracy

The model predicts therapist interactions for the patient with a high degree of accuracy.

Error histogram for predictions vs. therapist 1 joint position 1 data.

Each model option predicts with less than 0.1 radian (~5.7 degrees) root mean square error when compared to therapist data from various patients. Most deviation in the model predictions from true data is seen in the lower amplitude peaks of the gait phase, which already often occur from the exoskeleton inertia causing small oscillation rather than it being a part of the true gait. Like any machine learning model, erroneous predictions may occur with a large error. Protections are established within the code to prevent large predictions that may be out of the range of motion from occurring.

Dynamic Reconfiguration

The Synthetic Therapist was developed to aid in walking gait rehabilitation, which is a complex procedure that requires input from doctors and therapists to alter and change therapy to best suit the patient. As such, a variety of parameters can be adjusted during the course of rehabilitation, including the stiffness or perceived torque applied to the patient exoskeleton, a joint threshold for patients with limited range of motion, and the distance into the future the model predicts from ~3ms to ~75ms. The last parameter is used to make the Synthetic Therapist more or less anticipatory and leading of the patients motion, allowing varying amounts of guidance through the step.

Methodology

Data Collection

Data was previously collected for other studies in an exoskeleton dyad setup with post-stroke patients, so there as a suitable supply of data for the training of this model.

Data collection in exoskeleton dyadic setup. In each image, patient is on the left and therapist is on the right.

The data is a continuous file with two to four episodes of walking contained within, typically with a window duration of 10 minutes. The start of these episodes were determined based on which subject, the therapist or the patient, pressed a ‘synchronization’ button last, indicating that they were attempting to walk symmetrically. From there, the start was trimmed to be at the point of visual synchronization in the phase and approximate amplitude of the joints to capture only the desired synchronous walking. The end of each episode was determined by the subject who released the ‘synchronization’ button first.

Data Processing

With all episodes determined for all nine patient-therapist dyads, each set of data is concatenated to make one patient file and one therapist file of suitable data for each pair. For the model training-validation-testing pipeline, we chose to divide the data in a 70-20-10 scheme.

Division of data into training, validation, and testing sets.

For each patient and therapist, the first 70% of the data was used for training the model, regardless of total concatenated length. Each of the chunks of training data from all patients was conglomerated, as was the therapist data. From the patient data, the desired inputs were selected from the total sample collection, which are four joint positions and four joint velocities. The same selections are likewise pulled from the therapist data.

The model to be trained, a Long Short-Term Memory model (LSTM), utilizes a sliding window of memory referred to as a lookback window. The window is ‘sliding’ due to new data being added and the oldest data being removed at each step. Training used a specified lookback window of 50 timesteps or ~150ms. The feature for the model training is the patient data, with the target being the therapist data. The resultant shape of the feature and target is (50, 8) and (50, 1) respectively.

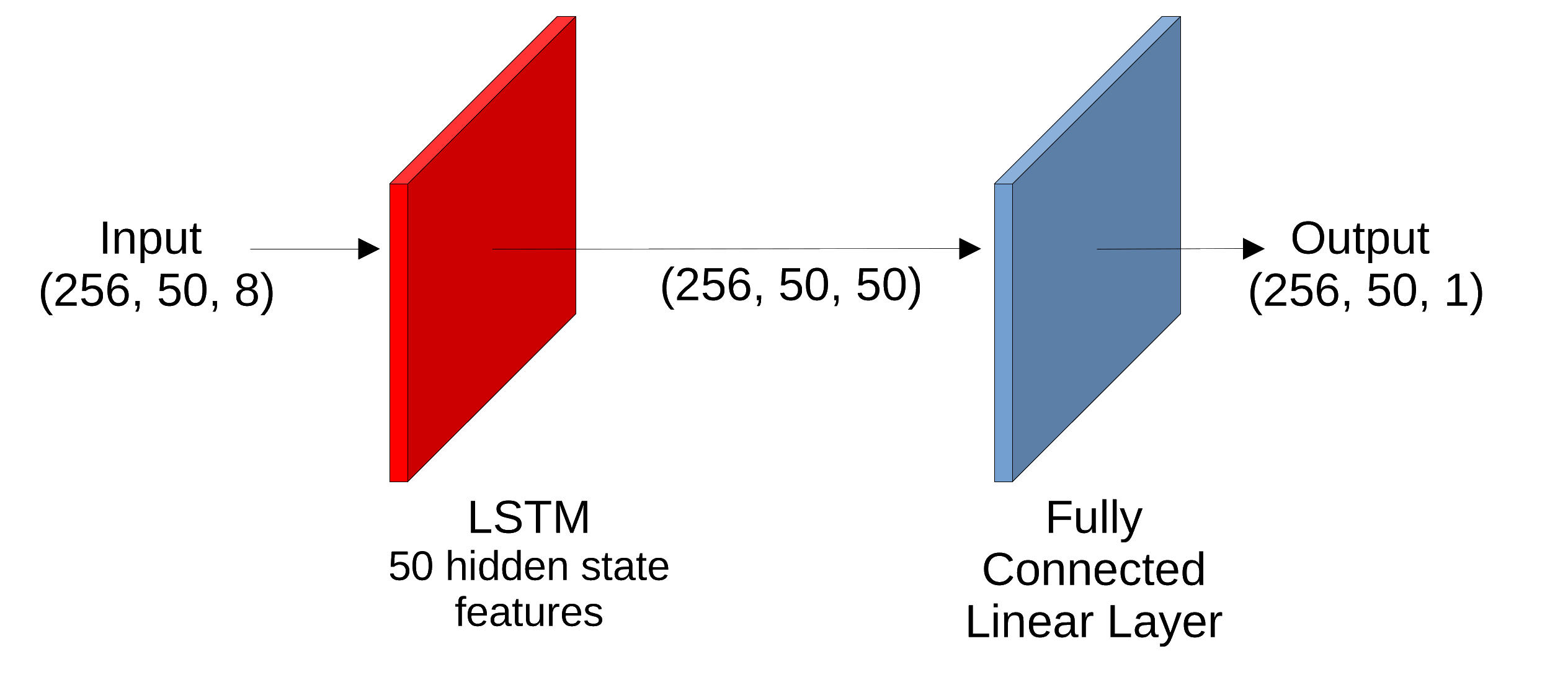

Model Architecture

To successfully predict therapist reactions for four joint positions and velocities, we implemented an approach using a number of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models. The final model for the Synthetic Therapist was created as a combination of PyTorch’s LSTM and Linear layer classes.

Example of model architecture.

Eight models were trained, one for estimation of each joint position and velocity of the exoskeleton. Each submodel’s LSTM used an input size of 8, hidden size or 50, 1 LSTM layer, and batched data first. The Linear layers had 50 input features and one output feature to properly connect to the hidden layers of the LSTM and produce a single output value.

Model Training

Each model was trained for 150 epochs, with validation run at each epoch, on the batched dataset with a batch size of 256, shuffled data, and a learning rate of 0.00001 within the Adam optimizer.

Example of training loss curve from training and validation procedure.

Training and validation datasets are constructed with the conglomerated patient and therapist data. For faster training, a step size of 5 was used during dataset creation to effectively reduce the dataset size five-fold. This adjustment to dataset size did not have a meaningful impact on model performance. This process is performed for both the training and validation sets to be synthesized.

With eight models trained, in the interest of reducing overall inference time, the models were then stacked and combined into one model. The stacked model utilized as input the same as each individual model - a lookback window of patient kinematic values of size (50, 8). This input was passed to each model in series, then the outputs of each model were combined into a singular output. The output tensor contains the desired values for the subjects joint positions and velocities.

ROS Integration

For implementation of the prepared model with the current exoskeleton dyad setup, a ROS node was created to handle functions of the Synthetic Therapist. Key components of this work were 1) proper usage of data for use as the input to the model, and 2) the assurance of real-time performance with the model.

For maintaining valid data in the simplest structure possible, we implement a Ring Buffer for data storage within the ROS node. The buffer has a maximum length of 50, matching that of the lookback window. Upon initiation of the node, patient joint data is appended to the buffer from ROS topic subscriptions until it becomes full. Only once full does the model begin prediction, as it requires the full lookback window size as input. Then, as new data arrives via the patient subscribers, the oldest data from the buffer is purged and the new data is added. This maintains the desired ‘sliding window’ effect desired for input into the model.

The main loop of the ROS node handles logic for calling the model for prediction and publishing the predictions for use in the patient exoskeleton control loop. When run on a Intel Core i9-14900HX CPU, the model had an average inference time of less than 3 milliseconds. As such, the node is limited in rate to 333 Hz to match the frequency of incoming data from the patient’s exoskeleton. This speed is ideal for the real-time nature of the system, although due to differing hardware when running the model within the exoskeleton workspace on a Intel Xeon(R) Silver 4210R CPU, the model is only capable of ~7 millisecond inference time. The slower hardware results in a prediction publication frequency of ~150 Hz. This decreased rate did not cause change in perceived forces during preliminary closed-loop tests, likely to it still being beyond human reaction time.

Collaborators

This project was done under the guidance of Lorenzo Vianello, a post-doc in the Neurorehabilitation and Neural Engineering Laboratory, led by Dr. José L. Pons at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab Legs + Walking Lab.